Note

Having every pipeline task in every job in a workflow read from registry and datastore and then write to registry and datastore does not scale when millions of jobs are involved. Instead we need an approach where the reads and writes are load-balanced to provide sufficient scaling. This note describes the issues and provides a possible design.

1 Introduction¶

When pipelines are executed by invoking the pipetask command, each PipelineTask that is executed results in calls to Butler.get() at the start to retrieve the relevant data and calls to Butler.put() at the end to write the results to Butler registry.

These reads and writes are run sequentially with the writes using separate transactions for each dataset.

If multiple pipeline tasks are involved in a single execution the registry reads and writes happen between each one.

In a workflow environment each job being executed currently uses a shared PostgreSQL registry and a remote object store.

The general scheme is described in [1] in the context of the Google Proof of Concept.

This approach works well until thousands of jobs are running simultaneously and they all need to connect to the database at the same time.

It’s also made worse if jobs take roughly the same amount of time to execute and they are all starting at the same time and completing at the same time and can lead to large connection spikes to the registry, leading to dropped connections.

We mitigated some of this problem in the Google Proof of Concept by spreading the start time of the initial jobs randomly over a ten minute period.

This smoothed out some of the spikes and allowed us to execute a few thousand jobs.

Unfortunately this approach will not scale when hundreds of thousands to millions of jobs are in flight at the same time and all trying to write to the same PostgreSQL server. It is also incompatible with a distributed processing approach where multiple data facilities are processing a fraction of the data and do not want to be reliant on one single server. We therefore need to change how we manage access to the registry and, possibly, datastores when we execute large workflows.

In the discussion below workflow is defined as a single submission to a workflow execution system, generally via BPS, involving the conversion of a QuantumGraph into distinct jobs that are executed on separate nodes.

Each job can consist of one or more quanta where chaining of quanta can be used where all the outputs of one quantum are immediately used by the subsequent quantum.

Currently jobs consist of a single call to the pipetask command.

2 Assumptions¶

The datasets created by the Rubin science pipelines are large and in a cloud environment it makes sense for the object store to be used directly by the Butler rather than attempting to use the workflow execution engine to stage the files to and from a workflow storage area to node local storage. Object stores are already designed to be efficient under load and should not cause any bottlenecks. This does not preclude using local cache for files that are the product of one quantum and the input to the next within the same job and it does not preclude a scenario where a shared file system is used instead of an object store.

In this document it is assumed that the workflow execution is run with the credentials of a service account that can do direct connections to the object store and cloud database. The batch submission system would check that the user submitting the workflow has permissions to read from the input collections and write to the output collection. Workflow executions using the standard infrastructure will never attempt to delete datasets from registry. If jobs are being executed with science platform user credentials it will be necessary for the workflow execution system to use the client/server Butler interface ([2]) which may result in an additional bottleneck to the registry and will require significant usage of signed URLs.

3 Reducing Registry Access¶

When running at scale the datastore reads and writes involving S3 or Google Cloud Storage are robust and load-balancing is handled natively by the cloud infrastructure. With a single PostgreSQL registry where all jobs must see an up-to-date view of the registry, reducing connections to the database, the number of transactions running inside the database, and the length of those transactions is critical when attempting to run with hundreds of thousands of simultaneous jobs.

There are many different points at which we can decide to do the registry updates and they are described below.

3.1 Immediate¶

The current approach used by the pipetask executor is to call butler.get() sequentially for each of the requested input datasets (sometimes this read can be deferred, for example when coadding many input images).

When the PipelineTask completes each of the output datasets is then stored in the butler with a butler.put().

It will use the Butler it has been configured to use and in the batch system that is a shared PostgreSQL registry and S3-like object store.

One problem with this approach is that the Butler is designed such that the registry changes and the file writing must all be completed within a database transaction. This can result in the database transactions taking a relatively long time for large data files (which first have to be written to local scratch space and then uploaded to the object store). Long-lived transactions can cause trouble with database responsiveness when tens of thousands of connections are active.

There are also concerns, as expressed in DM-26302, that the connection management in Butler registry is non-optimal since it disables connection pooling in SQLAlchemy and currently a single database connection is maintained for the duration of each quantum’s execution.

3.2 Job-level Pooling¶

One approach to minimizing registry interactions is to use a local registry during the pipeline execution job and then to batch the registry writes once the pipeline(s) associated with that job finishes.

In this scenario the job would start by exporting the relevant subset of the global registry to a local file (in YAML or JSON format) and importing it into a newly-created local SQLite-based Butler. This SQLite database would still refer to the datasets in their original datastore location. The pipeline would then be executed using the local registry and would interact as before with the cloud object store. When the processing completes the newly-created records would be exported from the local registry and imported to the cloud registry. This would use the automatic transfer mode since the files are already present in the object store in the correct place. If the job fails it is an open question as to whether the datasets that were successfully created are synced to the registry or not.

If quanta are chained, with the outputs of one PipelineTask feeding directly to the inputs of the next within the same job, the datastore will be configured to do local caching and write the file locally as well as to the object store so that the next one would read the file directly.

Doing this would have the advantage that the object store writes are no longer linked to a long-lived transaction in the shared database. On the other hand, if the pipeline processing fails in some way it is likely that there will be files in the object store that are not present in the cloud registry. These files can be deleted in a clean up job or they can be ignored, allowing them to be over written. Regardless, if the node is pre-empted during processing after files have been written, the orphaned files will be present and there will be no associated registry entries so attempting to clean-up does not gain us anything other than saving storage space if that run is never used again. The execution system is already capable of over-writing an existing file if it is not known to registry and datastore ensures that the file name is unique for a specific dataId and run combination.

If pre-emption occurs during the final registry import it is assumed that there is a single transaction that will be completely rolled back.

The end result would be that the entire processing would have to be redone.

If the pre-emption occurs in the short time between completion of the registry import and the completion of the job, we should ensure that the pipetask command is configured to complete without action when the job is restarted.

3.3 Externalized¶

The most flexible approach is for the workflow generator to insert extra jobs into the workflow that handle registry merging and registry syncing.

A new job would be inserted before the initial pipeline jobs in the graph that downloads the initial registry state from the cloud registry and stores it in a SQLite file. This SQLite file would then be provided as an input to the first job. The pipeline job would use that SQLite registry and a GCS-with-local-cache datastore as described in the previous section. On completion the output collected by the workflow execution system would be an updated SQLite registry. If the next pipeline job only takes files from a single input job this SQLite file would be passed directly to the next pipeline job. If, on the other hand, the next job gathers files from multiple jobs, the workflow generator will insert a new job before it that reads all the SQLite files and merges them into a single output for that job. It can optionally also sync registry information to the cloud registry and trim the SQLite file that it passes on. This sync and prune could be a distinct job that can be inserted after the merge job in the graph. At the end node (or nodes) of each workflow graph a final job will be inserted that updates the cloud registry with the final state.

In this scenario pre-emption has no impact on registry state for pipeline jobs since they are running with an entirely local SQLite registry. Pre-emption still has to be understood in terms of the registry sync jobs and requires that the remote update of the cloud registry happens in a single transaction.

This approach allows the submission system to decide whether the registry is updated multiple times within the graph or solely at the end since the registry merging jobs can be configured to either merge the inputs and pass them on complete, or merge, sync and trim. A trimmed registry can not be passed on to the next job if the remainder has not been synced with the cloud registry because subsequeny sync jobs will not be able to add the earlier provenance information since they will not have it.

3.4 Prepopulated Read-Only SQLite Registry¶

When a quantum graph is constructed the graph builder knows every single input dataset and every output dataset and how they relate to each other. The graph builder also knows the expected URIs of all the files created by the pipelines. This knowledge could be used to construct a SQLite registry that could be constructed by the graph builder and provided to each invocation. BPS could for example upload this SQLite file to object store and provide a URI to each job to allow it to be retrieved. This static file would then be passed to every job being executed and importantly, unlike the externalized approach above, it will never need to handle merging of registry information during the execution of the workflow graph.

On butler.put() the implementation would check that the relevant entry is expected but otherwise not try to do anything else.

The datastore would also write the file to the object store and interact with registry but might not write anything to registry itself.

Datastore would need to be changed to allow it to read the output URI directly from the registry to ensure that the expected output URI matches the one chosen by datastore.

This should be possible with a minor refactoring and is somewhat related to the refactoring that will be required to generate signed URLs from the URIs.

An alternative is to change the way that pipe_base interacts with Butler such that it no longer uses native Butler calls but instead uses a specialized stripped down interface.

On completion of the workflow the registry information can be handled in two ways:

- As for the externalized approach, insert a new job at the end of the workflow graph that adds the registry entries into the main registry.

- On workflow completion send the registry file to a queue that can integrate the entries into the main registry.

The first ensures that workflow completion coincides with registry updates but could lead to an arbitrary number of these jobs attempting to sync up with the main registry simultaneously. The second decouples workflow completion from registry updating and allows a rate-limited number of updates to occur in parallel. This would lead to a situation where a workflow can complete but the registry it out of date for an indeterminate period of time and would delay submission of workflows that depend on the results. Were that to happen though, it would be indicative that letting each workflow attempt the sync up directly at the end would be risky. Using a queue also completely removes registry credentials from workflow execution since the queued updates would be running in a completely different environment. Some workflow managers can limit specific jobs to specific nodes and doing such a thing with the sync job could automatically enable rate-limiting whilst guaranteeing that workflow completion corresponds to an up-to-date registry.

The synchronization must check that a corresponding dataset was written to the object store since it is possible for a workflow to partially complete and synchronization should (optionally?) happen even on failure since that can allow resubmission of the workflow with different configurations and also allow investigation of the intermediate products.

The limited registry approach still requires that the butler is interacting with an object store and would require the use of signed URLs if the datasets were being written to their final location in the shared datastore. If the signing client becomes a bottleneck an alternative could be to use a temporary bucket specifically for that workflow.

The synchronization job would therefore also need to move the files from the temporary location to the final location.

3.4.1 Implementation¶

The initial prototype implementation (completed as of w_2021_40) does not include URL signing since all Data Preview 0.2 workflow executions will be run by staff.

This included:

- Adding a

buildExecutionButlerfunction topipe_baseto create a prepopulated SQLite registry from the constructed quantum graph. Initially this registry could ignore the datastore table completely. - Adding a new

Datastoremode that no longer queries registry onDatastore.get()but instead assumes that the active datastore configuration (read from the user-supplied Butler configuration) would give the correct answer (something that can not be relied on in general but can be relied on in this limited context) for file template and formatter class. ForDatastore.put()it is entirely feasible for this to write to the standard registry (assuming it’s not entirely read-only) as is done now even if that write does not make it to the subsequents jobs; this does not affect the gets from downstream jobs because those will always assume that a get is possible. - Adding a

Butlerconfiguration option indicating that registry interactions can be skipped and assumed to be valid for fully-qualifiedDatasetRef. - Writing a new

butler transfer-backsubcommand to simplify the special case of exporting the registry from the SQLite file and importing it into the original registry. This checks that the referenced datasets are actually present in the expected location. - Update BPS to insert a special job at the end of the workflow graph that will run this merging code.

3.4.2 Analysis¶

Whilst the job-level pooling and externalized approaches would help with registry contention, the prepopulated read-only SQLite registry approach is much simpler. This removes any worries about merging the outputs of multiple jobs and lets us leverage the knowledge already known to the graph builder.

This approach does not scale well with QuantumGraph size, however; the SQLite file carries roughly the same content as the serialized QuantumGraph (easily a few GB for large graphs), and hence the cost of transferring this file to a single-quantum job can easily exceed the runtime of the job.

It also has four more subtle drawbacks:

- It redefines the boundary between

RegistryandDatastore(as mediated byButler), introducing branching and other complexity into (at best)Butlermethods or (worse) higher-level middleware tools, which now need to be able to work with eitherRegistryorDatastoreas the authority on dataset existence. - It forces

Datastoreto be able to work in a “prediction-based read” mode, another source of branching and complexity. - It relies heavily on object-store existence checks, both during execution and when transferring datasets back to the main data repository, to test whether predicted outputs were actually produced. Many of these checks are redundant, and they involve an operation that object stores are necessarily not designed to perform efficiently.

3.5 Limited Quantum-Backed Butler¶

Our Quantum data structure already has almost all of the information that we need to obtain from the SQL database during execution, especially if we can have Datastore reads operate in the “predicted records” mode introduced in the previous section, at least in the case of intermediate datasets written as part of the same submission (and hence using the same Datastore configuration).

In particular, Quantum is missing only

- the

Datastoreinternal records for overall-input datasets; - the dataset IDs for intermediate and output datasets.

If we can add these to the Quantum class (and its serialized form inside a QuantumGraph), we can implement the Butler read interfaces used during execution via an object backed only by a predicted-records-mode Datastore and a Quantum instance.

For the limited Butler.put operation during execution, we can call Datastore.put directly; when execution of that Quantum is done, we can then choose to either:

- discard the resulting

Datastorerecords; - save the resulting records to a per-

Quantumfile in an object store (possibly via theDatastore, possibly via directButlerURIusage, probably in JSON or SQLite format).

In the first case, the transfer-back job closely resembles the one described in the previous section, but with the potential datasets to be transferred obtained by iterating over the datasets QuantumGraph, not a prepopulated SQLite database.

Like the prepopulated SQLite database method, though, we must perform per-dataset existence checks and regenerate the Datastore records to be inserted after execution completes.

In the second case, the transfer-back job instead iterates over the quanta in the QuantumGraph, fetches the per-Quantum output files, and transfers their content to the database.

This could be much more efficient when the number of output datasets per quantum is large (one object store fetch vs. many object store existence checks per Quantum).

It also opens the door to writing provenance data and supporting new Datastore implementations during execution (e.g. a TableDatastore that writes a single-metric-value dataset to a row in table, not a full file).

Ideally the provenance information would also be transferred back to tables in the shared repository database, once schema changes make this possible.

For the rest of this section, we will assume (2).

3.5.1 Implementation¶

The classes described on this section have been prototyped on the DM-32072 branch of daf_butler.

- Define a new LimitedButler abstract base class for

Butlerthat defines only the operations needed for execution; these all operate on resolved references only. This includes newputDirectanddatasetExistsDirectmethods that write datasets with a pregenerated UUID and test for dataset existence given a resolvedDatasetRef, respectively. LimitedButler abstracts over the questions of whether datasets are being managed by aRegistryand whetherDatastorefalls back to prediction-based read mode, hiding the answers from all higher-level code; in the mainButlerimplementation of these methods, a sharedRegistryis assumed and records are never predicted. - Add a DatastoreRecordData struct and methods that can be used to export datastore opaque records, and attach it to

Quantum. - Extend

QuantumGraphconstruction to generate random UUIDs for output datasets (including intermediates) and extract and saveDatastorerecords for input datasets (including prerequisites). - Add a QuantumBackedButler implementation of LimitedButler with no

Registry, with itsDatastoreallowed to fall back to prediction-based reads. This mostly just needs to provide aDatastoreRegistryBridgeandOpaqueTableManagerto support theDatastore, with any writes the opaque tables serialized to per-quantum files by a method that will be called when a quantum finishes executing. - Modify

SingleQuantumExecutorandButlerQuantumContextto use optionally construct and use aQuantumBackedButler, and to stick to theLimitedButlerinterface even if they have a fullButler. - Write a new

transfer-backoperation that iterates over the quanta in aQuantumGraph, fetches the per-quantum records files, uploads theirDatastorecontent to the shared database, and insertsRegistryrecords for all datasets actually written. Note that this requires combining data ID information from theQuantumGraphwith UUID-keyed data from the per-quantum files. Much of this logic has already been prototyped as part of QuantumBackedButler_.

3.5.2 Analysis¶

This approach directly addresses the scaling problem with the previous approach, because our QuantumGraph I/O system already supports per-quantum reads, and there is no SQLite database to transfer.

With implementation described above, it can also mitigates some of its other problems, by encapsulating the different modes of operation and component boundaries behind the LimitedButler interface.

And while object-store existence checks are still used heavily by SingleQuantumExecutor, they are no longer necessary for transferring datasets back to the shared database.

A future extension in which opaque records are written to a scalable NoSQL database during execution instead of per Quantum files would also permit those object store checks to be replaced by lookups against that database, without any changes to higher-level middleware (just new LimitedButler and OpaqueTableManager implementations).

One possible weakness of this approach is that using LimitedButler as the interface that backs execution may ultimately be temporary: we may someday never want to use the main SQL database to back execution (even in standalone pipetask run invocations).

Making production of data products distinct from “publishing” them to others could be valuable functionality, especially for public data repositories with many science users, and it could provide a useful paradigm for a much-needed pipetask interface overhaul.

In such a future, SingleQuantumExecutor and ButlerQuantumContext could just use Datastore interfaces directly, because they would always be operating on the assumption that datasets are being written only to a Datastore, and identifying whether a predicted dataset actually exists is wholly a Datastore responsibility as well.

Finally, this approach makes some conceptual breaks with the past that seem like good moves, but nevertheless merit some attention.

First, it moves arguably the most important source of dataset UUIDs out of the butler and into QuantumGraph generation (or at least into a butler/registry convenience method that can bee called by QuantumGraph generation).

Up to now, we had considered UUID generation to be strictly a butler implementation detail, in part because of a desire to support legacy data repositories with autoincrement integer IDs, and in part out of a healthy tendency towards encapsulating things higher-level code shouldn’t have cared about.

If we take this approach to batch execution, we will be relying directly on UUIDs (in particular assuming that UUIDs generated for one QuantumGraph will never collide with datasets written to the main repository while it is being executed), and any previously “nice-to-have” guarantees about IDs not being rewritten become hard requirements.

Second, it breaks our past association of resolved DatasetRefs with dataset existence; QuantumGraph objects will now be populated with exclusively resolved DatasetRef objects, making it quite easy to obtain resolved references to datasets that were predicted but were not produced (or have not yet been produced).

Datastore existence (either via file checks or internal record checks) is now more firmly the only way to tell what actually exists.

We had already started down this path with prepopulated registry approach, but it is worth taking a moment to consider where it will take us.

Two additional advantages of this conceptual approach stand out:

- By assigning UUIDs even to predicted-only outputs, recording provenance will be much easier - we can use the same kind of dataset ID for all links, instead of having to invent a new kind of ID (or rely exclusively on data ID +

RUN+ dataset type) for datasets never actually written. - By removing the most prominent source of unresolved

DatasetRefobjects (actually the only production - rather than unit test - source I can think of), we may be able to make massive simplifications to theDatasetRefclass and all of the code that uses it (which currently has to constantly check for whether refs are resolved). We may even be able to simplify theButlermethods that currently takeDatasetRefobjects; if we have*Directvariants that require resolved references, perhaps there is no need for the non-direct variants to acceptDatasetRefobjects at all.

On the other hand, in order to bring predicted-only provenance back to the shared database, we will need to actually have regular Registry entries for those predicted-only datasets.

These would be confusing for users if we didn’t keep them from appearing in queries by default.

Transferring them into different RUN collections could be a decent stopgap (and we don’t need to include them in Registry at all until we put provenance in the Registry), but finally providing good query support for “only datasets that exist in a Datastore” feels like a much more complete and natural solution.

The table intended to back those queries - dataset_location - is something that has long felt underdesigned and perhaps premature; it will probably need work if it suddenly becomes much more important.

This may be an opportunity to fix other problems, however; the messy transactional relationship between Registry and Datastore (especially as regards deletion) is predicated on the assumption that datasets must exist in a Registry in order to exist in a Datastore, and dataset_location is at the center of that.

Embracing the idea that datasets may exist in either Registry or Datastore (or both, of course) may provide useful simplifications.

3.5.3 Transition from Prepopulated Registries¶

The implementation plan for this section does not include trying to simultaneously support the existing prepopulated registry method, as I think we want to retire that as soon as we have another approach available.

For a short period, just using if guards to allow both approaches to coexist makes sense, even if the legacy prepopulated registry support violates some of the behavioral guarantees of the new ABC.

Another approach that may be better for continued support of both approaches would be to implement a new LimitedButler subclass to be backed by a prepopulated registry, which should reduce or even eliminate the need for other middleware code (specifically SingleQuantumExecutor) to be aware of the mode in which execution is occurring.

3.5.4 Performance¶

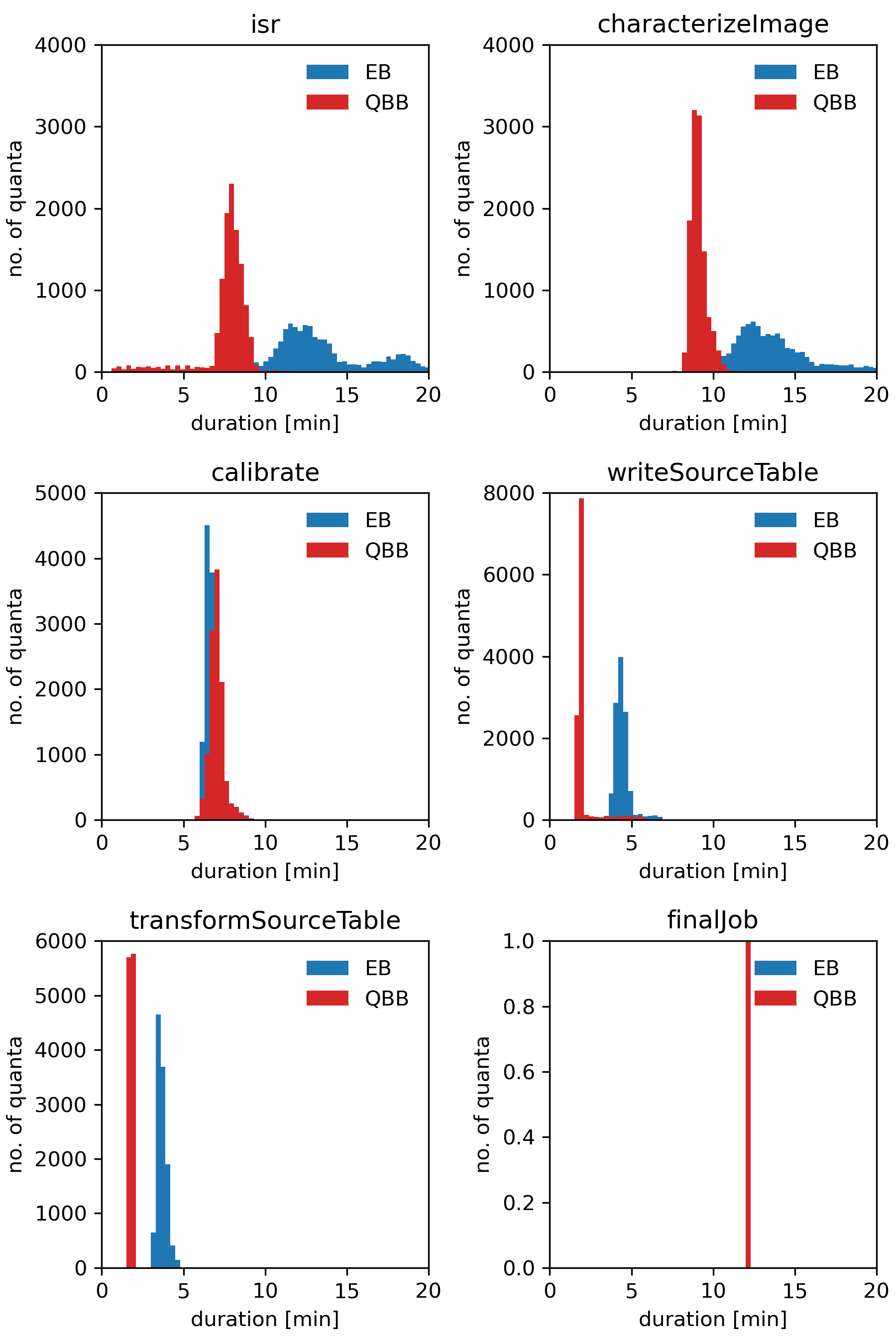

To compare overall performance of the execution and the quantum-backed butler we selected Step 1 on DC2 test-med-1.

For each run, the workflow consisted of 57,305 quanta distributed evenly between five tasks: isr, characterizeImage, calibrate, writeSourceTable, transformSourceTable.

Rubin’s BPS added two more jobs to the workflow: pipetaskInit and finalJob.

Both runs were made at USDF with BPS using the HTCondor plugin.

Figure 1 Distributions of job durations grouped by pipetask name. Blue histograms depict time distributions for workflow execution which used prepopulated read-only SQLite registry also known as the execution butler (EB). Red ones show corresponding results for the workflow which used quantum-backed butler (QBB). In both cases, job duration was calculated as the difference between the start and the end of an HTCondor job. All reported times are in minutes. As the execution times of the final job for EB and QBB were practically identical (~12 minutes) the corresponding bars overlap to such an extent that only one of them (for QBB) is visible on the plot.

Note

For pipetaskInit its duration was approximately 42 minutes when using the execution butler and only 2 minutes when using the quantum-backed butler.

However, we didn’t observe similarly large discrepancies for other (though smaller) runs.

As a result, we decided to exclude it from the report.

Most likely the large difference was caused by some transient, external factors affecting the execution of the HTCondor job running the task.

These runs demonstrate that the quantum-backed butler is faster than the execution butler and results in much more stable job durations that are now dominated by the processing time and not by the unpredictable times from copying the SQLite file to each node. Using the quantum-backed butler also significantly speeds up BPS submission as there is no need to create a SQLite registry which takes a significant fraction of the submission time for large workflows.

References

| [1] | [DMTN-157]. Hsin-Fang Chiang and K-T Lim. Report of Google Cloud Proof of Concept. 2020. LSST Data Management Technical Note. URL: https://dmtn-157.lsst.io |

| [2] | [DMTN-176]. Tim Jenness. A client/server Butler. 2021. LSST Data Management Technical Note. URL: https://dmtn-176.lsst.io |